Pongo Points:

• The crypto industry is constantly seeking ways to divest itself from the traditional finance world, but is stuck in two key areas: Exchanges to and from fiat currency, and stablecoins. While the former is impossible to separate from traditional finance, stablecoin experiments have become bolder and more convoluted over time.

• "Centralized stablecoins" are essentially US dollar-pegged products offered by companies seeking to improve liquidity and other critical functionalities in the crypto space. They are often attacked because of the structure of their businesses (i.e. they aren't decentralized), but are widely recognized as essential cogs in the machine.

• "Decentralized stablecoins" are products that attempt to peg a token to the US dollar through various flavors of derivatives. This includes Terra, which failed due to its collateral faltering and an unsustainable issuance scheme, and Ethena, a newcomer project that pegs to the dollar using Ethereum derivatives. Oftentimes, these products fail because of one specific confluence of events (which happens to be the product's exact crux).Fiat Functionality

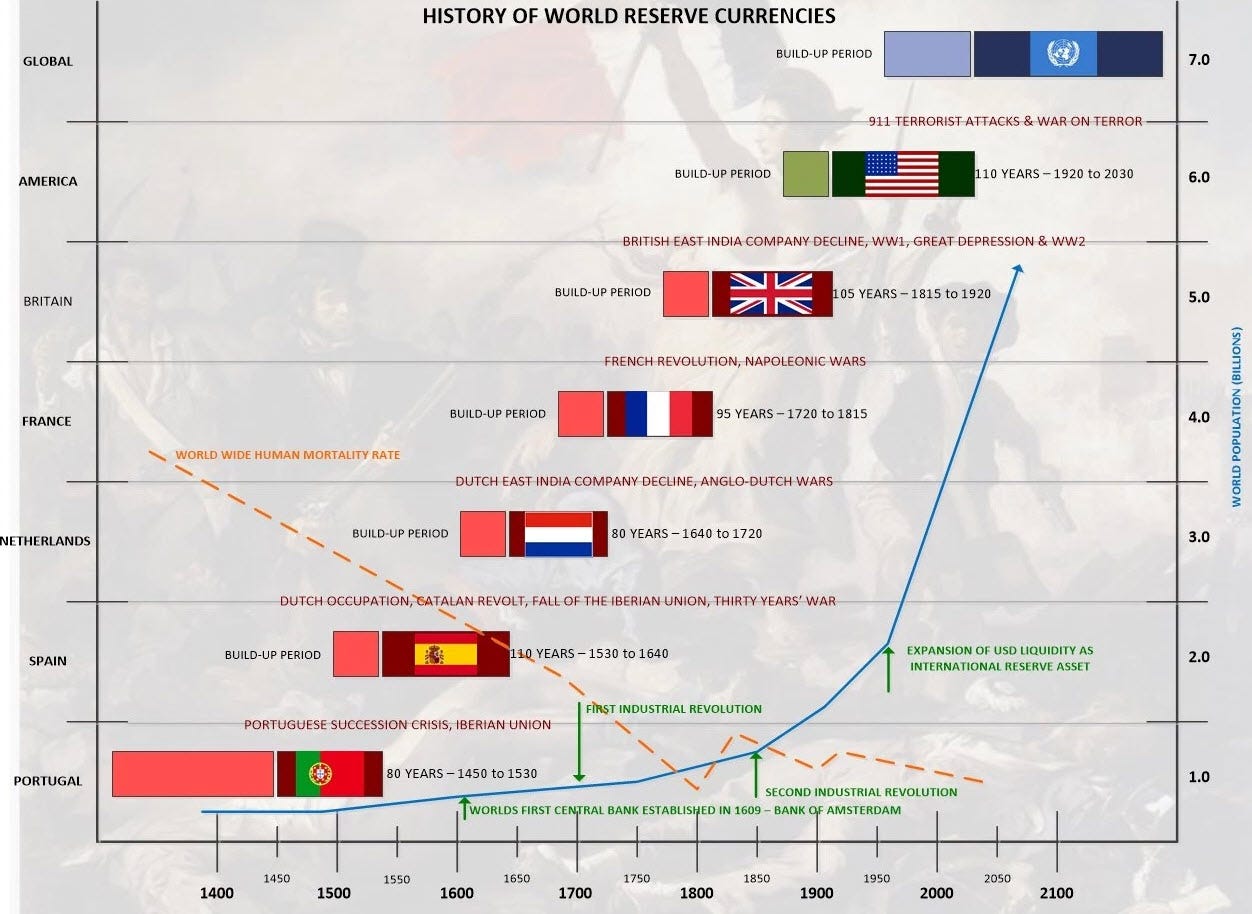

Crypto advocates love to talk about how fiat currencies, like the US dollar or the euro, will inevitably fail due to the corrupt individuals and agencies that manage them. They aren’t wrong necessarily: See the collapse of the British pound sterling, the French franc/assignat before that, and the Dutch guilder before that. Practically every global reserve currency has failed due to actions made by a few people; be it a wartime agreement among desperate allies (i.e. the Bretton-Woods system) or poor fiscal policy (i.e. printing more money than a government has assets).

Bitcoin differentiates itself from fiat currencies in that the rules of its issuance and collateral are ruled by the majority, rather than a minority. Does it have the potential the become a reserve asset? Perhaps - but, in the meantime, most people still want to trade in and out of fiat currencies to live day to day. And for that, we have stablecoins.

Stablecoins are tokens on a blockchain that are pegged to a fiat currency. (There are tokens for the euro, yen, etc., but most stablecoins are pegged to the US dollar which is what I’ll be referencing from hereon.) They enable more convenient ways for “on chain” traders to move in and out of crypto tokens that are only available on decentralized exchanges, or simply provide access to the US dollar where it might be otherwise restricted (see Argentina). For all intents and purposes: It’s the US dollar on a blockchain.

The way these stablecoins are created generally falls into two categories: Centralized and decentralized. Centralized stablecoins are issued by a company that controls the collateral backing them, typically US T-bills, corporate debt, or other traditional financial instruments. Decentralized stablecoins are issued by a DAO or automated process, and tend to be over-collateralized since they are often backed by Bitcoin, Ethereum, or other cryptocurrencies. Let’s explore the pros and cons of each.

Corporate Cash

The most popular stablecoins by far are centralized. In other words: Companies generate tokens on a blockchain that can be redeemed 1:1 for a dollar, euro, yen, etc. and vice versa. It’s the most efficient way to be able to use dollars on a blockchain and also happens to be one of the best use cases for blockchain generally (so far). Many stablecoin users have no interest in blockchains, crypto, or other tokens, but instead use stablecoins to evade strict capital controls.

The leading firms in the stablecoin space are Tether ($USDT) and Circle ($USDC). Each company manages their cash reserves differently, but generally invest in highly-liquid and short-term bonds so that they can quickly accommodate withdrawals. As of the time of writing, the two companies manage approximately $150 billion US dollars worth of stablecoins (as well as a few hundred million in other fiat currencies). By comparison, the third largest stablecoin manages about $5 billion USD worth of assets.

What are the shortcomings to this form of fiat currency? Many crypto proponents point to centralization (or “custodial risk”), which is, frankly, a weak argument. The thought is that the managers of these firms can lie about or steal from the large corporate treasuries that they manage. Sure, there are fraudsters that have managed large sums, such as Enron or Nikola, but the market tends to weed out illegitimate companies over time. To suggest that every stablecoin issuer is prone to fraud implies an issue with the industry rather than the players.

For the past several years and for the foreseeable future, centralized stablecoin issuers are the simplest and most reasonable way to put US dollars on the blockchain. However, for those who have a higher risk tolerance and require less human oversight, there do exist “decentralized” stablecoin issuers. These come in the form of blockchain experiments that effectively function as large credit facilities. What could go wrong?

Decentralized Dollars

A large contributing factor to the rapid price decline for most cryptocurrencies in 2022 was due to Terra. Terra was a blockchain protocol that issued stablecoins based on an algorithm and was, in theory, “decentralized.” Anyone with half a brain could see that their issuance schedule was unsustainable, but, unfortunately and unsurprisingly, around $45 billion of brainless-owned money was lost in a week. Terra’s scheme was essentially this: Buy our token, we’ll give you a 20% return on it if you loan it back to us, and we hope the music never stops.

Undeterred by the failure of one algorithmically backed stablecoin, the crypto industry went to work on newer and more complex protocols. The latest version is called “Ethena,” and promises to “enable the internet bond” by issuing stablecoins pegged to the US dollar via protocol-held collateral and hedges. In other words: Give us your tokens, we’ll give you a 37% return on it, and we hope the music never stops. Sound familiar?

The core difference between Terra and Ethena is how risk is managed. Terra’s model was very circular, since any promise of a return generally required the use of their token as collateral - which was unhedged. Ethena’s model differentiates itself by accepting different tokens as collateral (although it only accepts Ethereum as of the time of writing), and hedges against price volatility with derivative contracts. The pivotal failure is that they both use highly volatile risk assets as the only collateral to support a peg to the US dollar.

Other forms of Ethena have existed (see Aave, Maker, and Compound), but they manage risk with overcollateralization rather than hedging (which is capital inefficient). Ultimately, stablecoins have tradeoffs, whether its hedging with derivatives, overcollateralization, or custodial risk. For now, I’d rather trust a company to play nice than to hope volatile collateral does.